Part I - Quick history of information

To understand where we are today and where are we heading, we have to understand where are we coming from.

In early December of 2022, I wrote an article about AI titled ChatGPT and AI Snapshot. Now, over a year and a half later (and a bit), it seems like a good time to take another snapshot. Since then, I’ve fine-tuned models myself, built on top of vector databases, and developed AI pipelines to extract and structure information on a large dataset. This new snapshot will consist of several blog posts, with the first focusing on the history of information.

Part II - Compression of knowledge

Part III - Master of puppets

Understanding information

Everyone seems to be consumed with AI now—how it will change the way we live, transform our lives, or, depending on your bubble, even destroy us. To understand AI, we need to understand how we’ve reached this point and how information, in general, has shaped humanity over time.

Before diving into history, we need to establish some metrics (because we’re data-driven) so we can compare information. These are the metrics I’ve chosen:

Latency: The speed of information distribution. How fast does information travel?

Novelty: Does it contain new information that can change the way we think and operate?

Authority: Does this information come from a trusted source?

Precision: Do we all have the same “picture”?

Of course, there are different ways to look at this, but these are the dimensions I’ve chosen.

For the record, this is a rough sketch of the history of information and not a factually accurate representation.

Let’s dive in! Might be boring at the beginning, but it will get intense. I promise.

In the beginning there was a word

Okay, this is the beginning of my history of information.

Humans began sharing a lot of information through words. Like children, they initially mumbled, but eventually, they started to be understood. Parents understand their children before they actually make sense. "Moeh ma bhrd!" "Awww, the little one wants a piece of bread?"

Our metrics:

Latency: Word of mouth travels at the speed of walking. The more people you meet, the more you share. It’s pretty slow.

Novelty: Questionable, but it certainly contained new information. Sharing details about weather, rivers, hunting spots, etc.

Authority: Depends on the speaker. If it comes from that very old person (probably 35), it’s valuable, as they’ve been around for a long time. Very old, very wise.

Precision: Very low. Like playing a broken telephone game where you whisper something to the person on your right. It’s always wrong at the end.

Dumping information

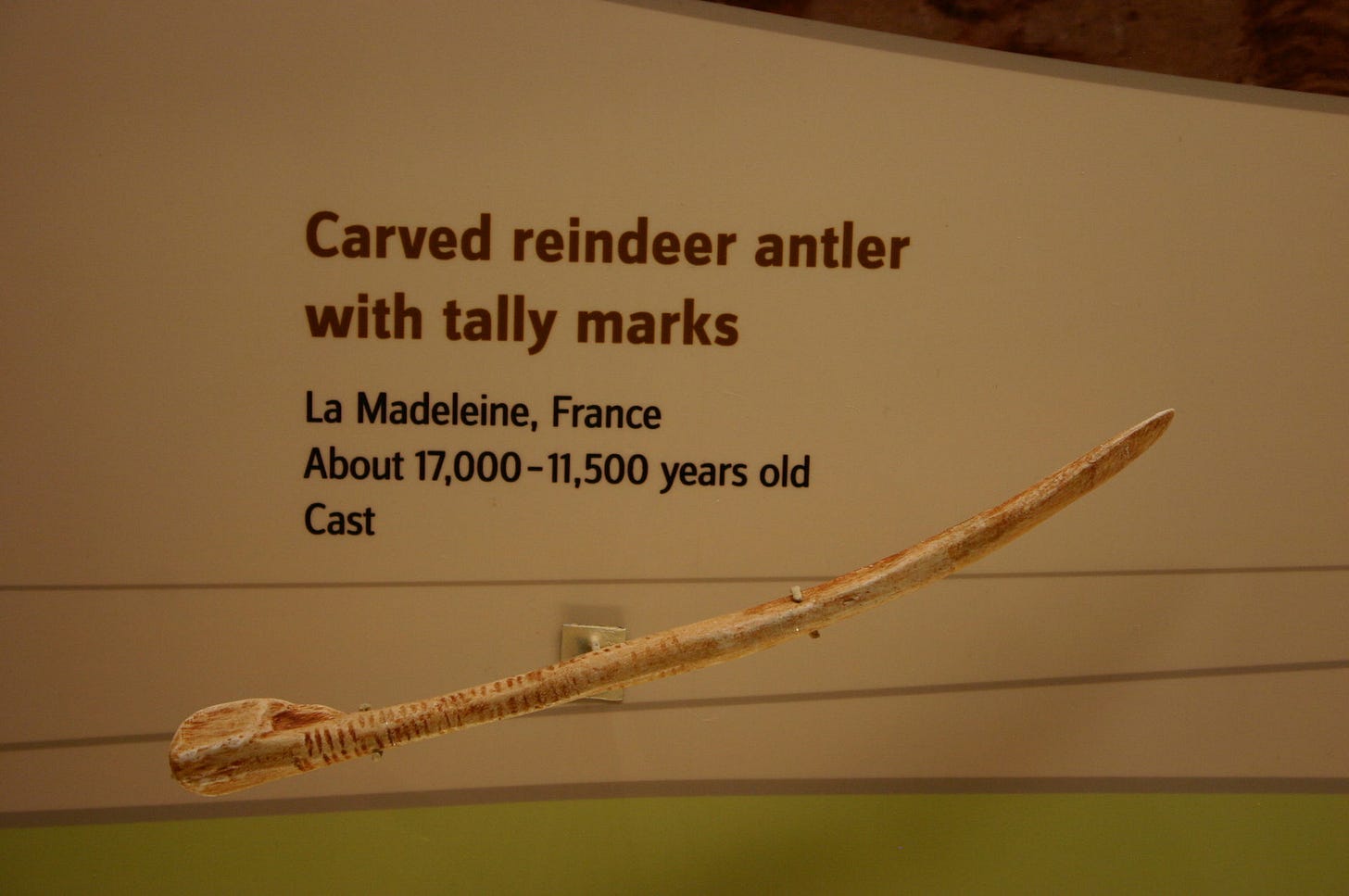

At some point, someone figured out that information needed to be “saved” for sharing and reuse. The first piece of written content was probably in the sand, like computer RAM. It held information, but it was gone with the breeze.

Then someone, for whatever reason, decided to draw something on a wall. A “wall post” about five bison and one hunter. Someone spent the whole day leaving this one message on a wall by drawing it. But this already changes the dynamics of our information metrics.

Latency: Still slow. But now it’s asynchronous. Write once, consume for millennia to come.

Novelty: This medium is not the best for conveying complicated messages, particularly with symbols. Probably not containing very novel information.

Authority: We have no clue who drew it on the wall.

Precision: High. It is what it is! We all can look at this same picture and make up our minds. This is very good.

And thus, the first database is born—one record in one particular cave. You can visit it, check it out, and learn something new. A revolution has happened.

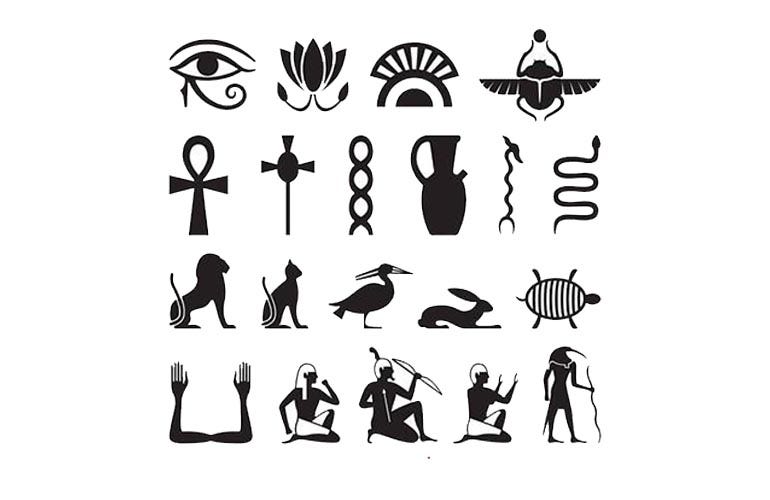

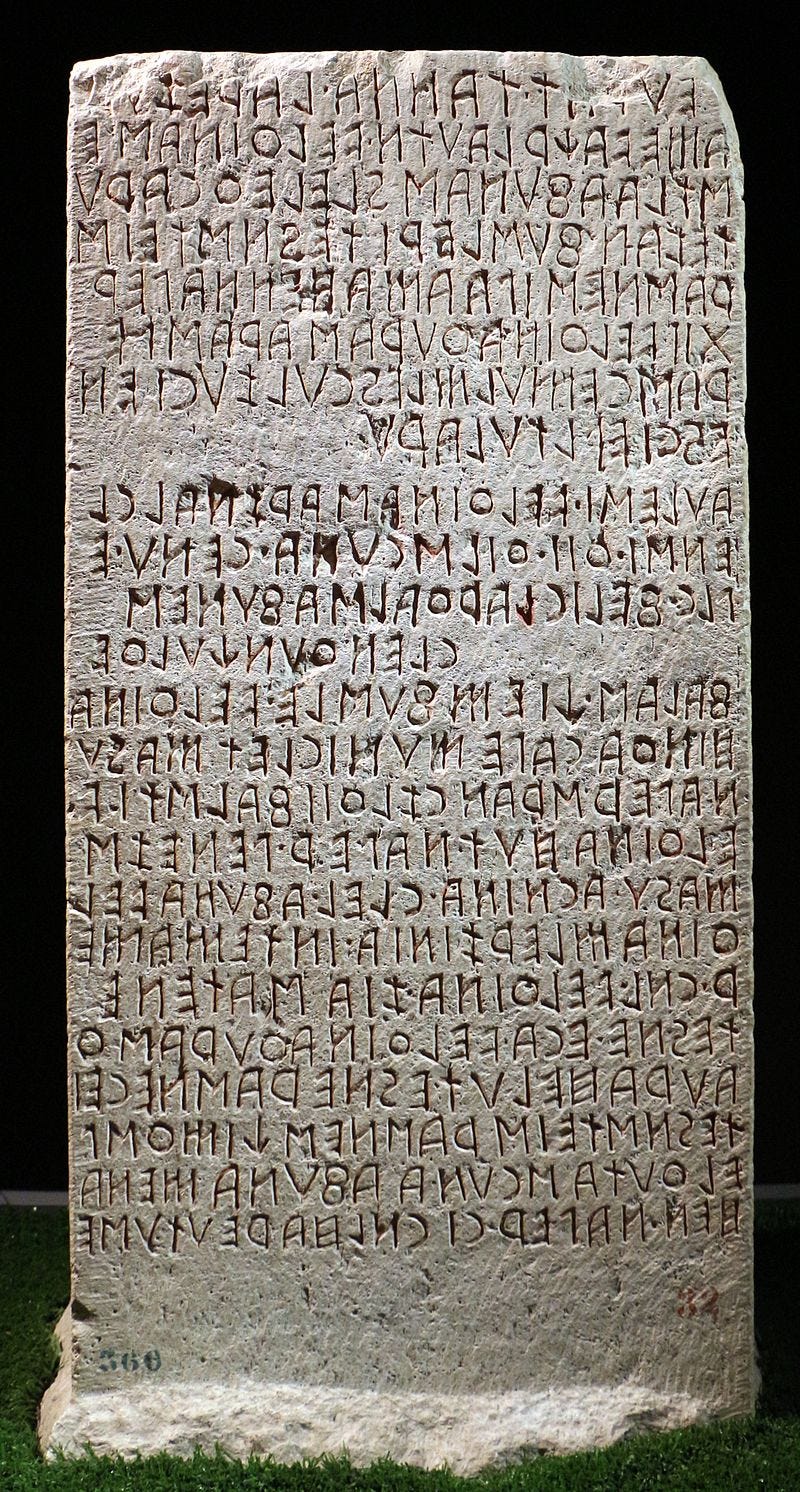

Symbols

Let’s take that drawing to the next level by introducing more symbols. What if we systematise it, like the Egyptians or the Mayans? Now, we have the ability to convey more complex stories because we’ve agreed on a system of symbols.

Latency: Still slow. You have to go to a specific place and check it out to learn something.

Novelty: Since we can "store" more complex information, we can convey more intricate ideas.

Authority: Only the nobles can do this, and they are sent from God anyway. They must know everything.

Precision: It’s carved in stone, so it is what it is. We’re still looking at the same piece of information thousands of years later.

Now, we truly have a database. You go there, and there are walls filled with symbols.

Numbers and money

Some information is quantitative and we can attach value to certain things.

Humans had to figure out special symbols for mathematics. Up until this point, the calculator was human fingers or sticks. But we needed to go beyond that as our world became more complicated.

Humans invented numbers and money for this specific task. It’s not language; it’s about a different aspect of our lives—value and quantity.

Latency: Everything is still slow here.

Novelty: Numbers allowed humans to quantify the world around them, from counting to figuring out that the world is not flat (we’ll get back to this one).

Authority: High authority. If you know numbers, you really know your stuff. Numbers don't lie.

Precision: It’s math.

These symbols start their own journey, and we will revisit them later.

Writing sounds

Symbols are cool, but they have limitations when it comes to conveying more complex or abstract information. What if we abandoned symbols altogether and instead assigned symbols to sounds? By inventing the alphabet, we could write everything down on paper. No more struggling with "I'm missing a symbol for the emotional state" moments.

Latency: Written words can move faster, so information travels faster too. However, you still need to know how to write and read, so not everyone can “share.”

Novelty: We’ve moved beyond simple symbols, allowing a vast array of ideas to be put into writing. This marks an explosion of novelty.

Authority: If someone can write, they are likely educated and considered smart.

Precision: With the ease of writing comes an increase in volume, but the precision of information can suffer. It’s not carved in stone anymore. People can copy ideas, add their own thoughts, and redistribute them. A lazy monk might skip a paragraph or add his own interpretation to the text.

This shift leads to an explosion of manuscripts. The Library of Alexandria becomes a kind of "server" where you can access vast amounts of information and ideas.

However, not everyone is happy about this innovation in writing. As with every technology break throughs, there are deniers.

Plato, apparently, was not impressed:

And so it is that you by reason of your tender regard for the writing that is your offspring have declared the very opposite of its true effect. If men learn this, it will implant forgetfulness in their souls. They will cease to exercise memory because they rely on that which is written, calling things to remembrance no longer from within themselves, but by means of external marks.

What you have discovered is a recipe not for memory, but for reminder. And it is no true wisdom that you offer your disciples, but only the semblance of wisdom, for by telling them of many things without teaching them you will make them seem to know much while for the most part they know nothing. And as men filled not with wisdom but with the conceit of wisdom they will be a burden to their fellows.

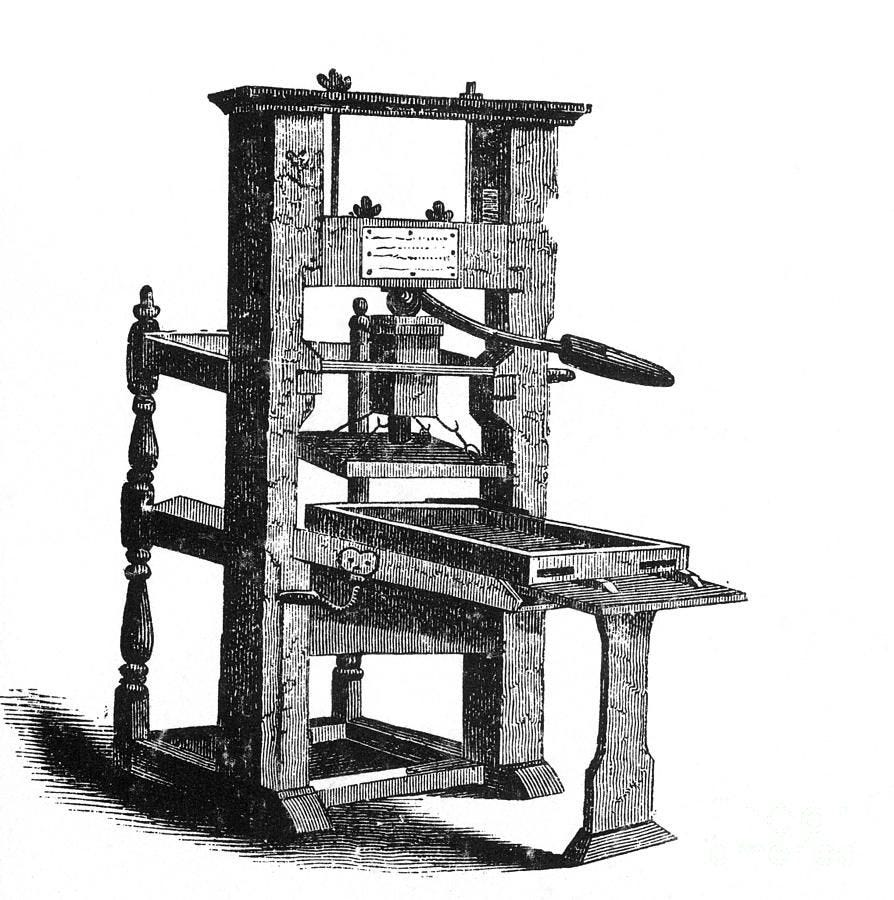

We have to go faster

With the invention of the printing press, we can now copy information quickly and efficiently. This is a game-changer. A lot more people can now access the same information.

Latency: Books can be shared and copied rapidly. One piece of information now has multiple roots to spread into the wider world. Ideas spread faster, significantly reducing latency.

Novelty: The increased volume of printed material leads to a surge in new ideas. Novelty is on the rise.

Authority: Reading and writing are still considered luxuries, so those who author books are regarded as very smart individuals with high authority.

Precision: We’ve returned to a high level of precision, similar to the days of wall drawings, but now with scalability. A single book can have exactly 1,000 identical copies. This marks a major breakthrough in precision.

Now, nobles can have libraries containing vast amounts of information. Ideas spread like wildfire throughout Europe, with people continuously dumping more information onto paper, sharing it, reproducing it, and sharing it again. The Renaissance is in full swing.

Photo, radio, television, telegraph

For several centuries, the written word ruled the world. But then came electricity, bringing with it the opportunity to reinvent information once again. This era also saw the introduction of photography, a medium not yet powered by electricity, but revolutionary in its own right.

Photography is a unique medium that captures the visual world as it is. The ability to "capture" a moment visually is mind-blowing.

With the advent of the telegraph, radio, and television, the latency of information was radically reduced. Information could now move at unprecedented speeds.

Latency: It’s fast. Mass media is born, and information can be disseminated quickly across vast distances.

Novelty: Before this, people told stories about places and people. Now, you can actually see them for your self. There is so much content and ideas now.

Authority: Broadcasting mediums were mainly supported by governments, which made them trusted sources of information.

Precision: It is what it is—one source spreading information to the masses, ensuring that the message is exact.

You no longer need to travel to Paris to see the Eiffel Tower, nor do you need to attend an event to experience it. The same piece of content can reach millions of consumers, broadcast from a government source that people still trust.

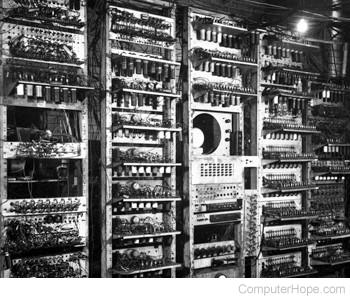

0 and 1

Our friends in the mathematics branch have been working diligently with their system of symbols and have come to a groundbreaking conclusion: the best abstraction for representing anything is a system of switches, checking whether they are on or off—whether it's 1 or 0. Enter the transistor!

With transistors, humans now have these incredible machines called computers that can perform mathematical calculations and store vast amounts of information. This is revolutionary. A computer can function like a library, holding numerous "books" of information, while also performing an astonishing amount of calculations. Up until now, the world—bridges, ships, the first planes, pyramids, the Eiffel Tower—everything was built with pen and paper. It’s almost unbelievable.

Latency: It’s not great. Information is largely locked inside your computer box.

Novelty: A vast number of ideas can be created and documented with these machines. Humans can now perform calculations that were previously impossible.

Authority: As computers become more accessible, we start to lose centralised authority. However, they are still mostly housed in universities, which are trusted institutions.

Precision: It’s incredibly precise. Each piece of information is exact. It’s easy to modify and reproduce, but due to the latency, it’s not happening as quickly.

Now we have this new abstraction: the more switches—transistors—we have, the more calculations we can perform. Humans are beginning to abandon paper, realising that we can achieve far more with machines than we ever could with pen and paper.

Most of the people now exchange understanding for efficiency. It just get’s the job done faster.

The network

We had these computers filled with information, but sharing that information was cumbersome. Copying data onto tapes, floppy disks, or CDs was slow and inefficient.

Meanwhile, the military and academic researchers figured out a new way to connect these machines. They realised that computers could be linked together over phone lines, allowing them to "talk" to each other. By giving each machine a special number to call, they could establish connections and share information across distances.

Latency: It’s improving. Now, instead of physically transporting a tape across the country, you can download the information onto your machine in a few hours.

Novelty: The novelty hasn’t changed much with networking itself, but the potential for new ideas to spread faster is beginning to emerge.

Authority: If you’re on the internet in this era, you’re likely part of a university or the military. These are trusted institutions, so the information shared is generally considered reliable.

Precision: Precision remains high. Information is still shared accurately. Slowly but precisely.

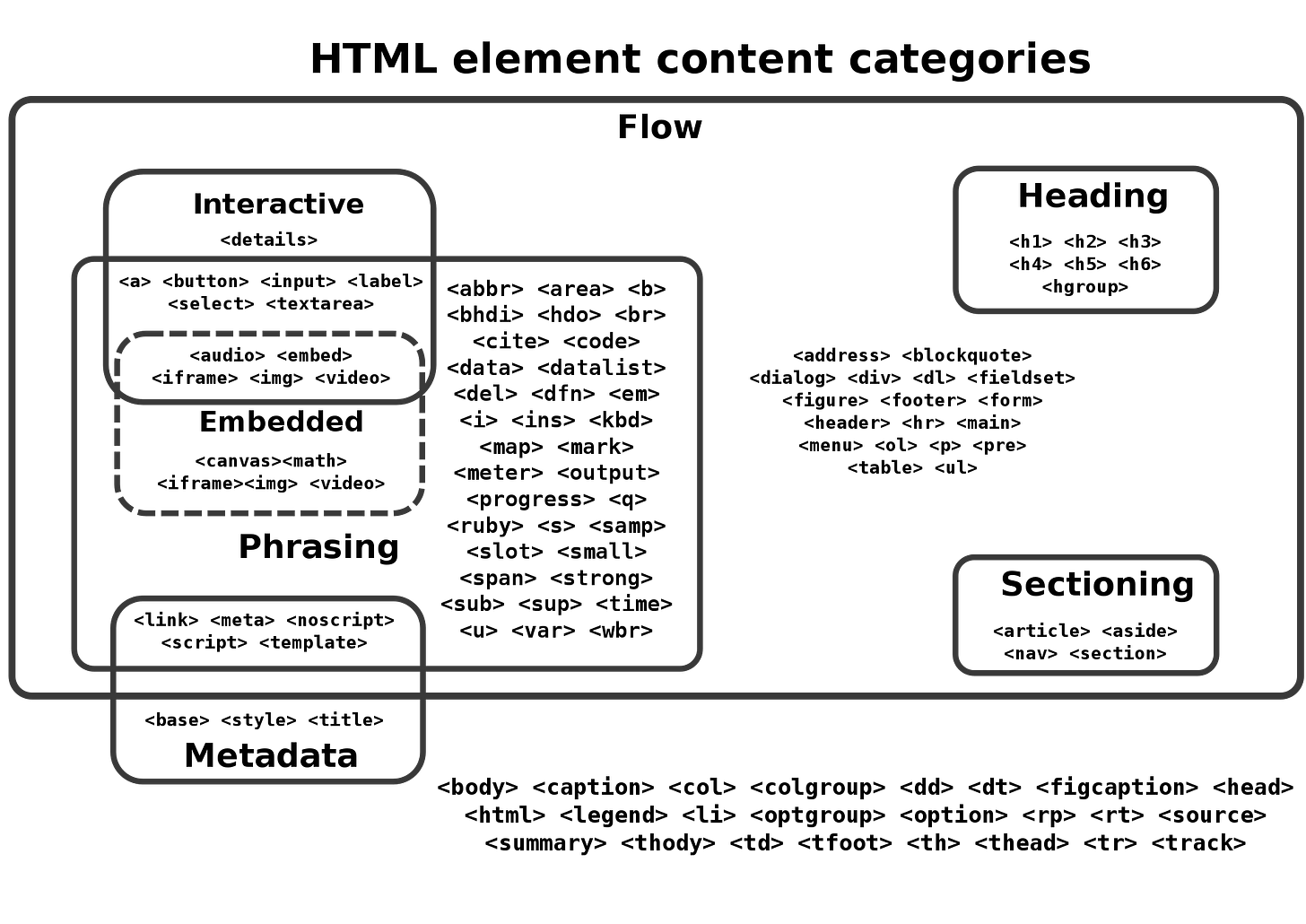

html

As machines became faster and more powerful, and the network continued to grow, the way we exchanged information evolved. You could now go online, download a piece of content, and view it on your machine. It was like connecting our own libraries, allowing us to jump from one to another. Amazing!

But what if, instead of using the internet merely as a means of transportation for data, it became the medium itself? What if we could create special kinds of documents ON the internet? Enter HTML (HyperText Markup Language). Instead of downloading content, you could use special software—a web browser—to view these HTML documents directly. And these documents could link to other documents. Minds were blown!

Latency: It’s instant. Just open it up and look at it in real-time.

Novelty: There’s a surge in novelty as it becomes incredibly easy to publish content. The barrier to entry is low, and creativity flourishes.

Authority: Authority starts to diminish as more and more people gain access to the internet. It’s so easy to produce content that anyone can publish anything. You know, "On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog."

Precision: Precision begins to suffer because of the sheer speed and volume of information. A single source can be accessed by many, but there are now countless sources, making it difficult to pinpoint a single piece of accurate information. Everything becomes a blend of ideas and perspectives.

This unleashed a kind of information balancing act. You can now read about anything—how to build an atomic bomb, why the Earth is flat, how to get rich, or how to have a successful career. It’s all out there, and the volume of content keeps growing.

People even began writing down the web addresses of interesting sites in notebooks, keeping a list of places to visit when "going online."

Search

As the volume of information grows, it becomes overwhelming. How do we find what we’re looking for in this vast sea of data? Enter search engines, and most notably, Google with its PageRank algorithm, which helps determine authority based on incoming links.

Latency: We nearly lost it. The sheer volume of information makes it impossible to consume everything, and without search, finding relevant information would be like looking for a needle in a haystack.

Novelty: While search itself doesn’t create novelty, it allows us to access new and valuable information more efficiently.

Authority: Google search represents another pact between humans and technology, similar to the one we made with computers. In this case, we’re making a deal with an algorithm. It’s no longer just about our judgment; we’re outsourcing it to Google and their implementation of the PageRank algorithm. With the speed of information flow and the constant influx of new content, we’ve had to trade some of our own authority for efficiency. We trust Google because its results are “better,”

Precision: There’s still a vast variety of information, but each piece of content is a distinct and exact piece, and everyone can access it in the same way.

Humans used to handle information themselves, carefully sifting through data (for most of human history - none at all) to find what they needed. Then came librarians—the original "manual algorithm" and "search engine" of a library. Google functions much like this librarian, except it’s library is whole internet. It returns a list of 20 "books", and you decide which ones might be useful (a lot of times based on a “cover”). We understand that this librarian relies on the PageRank algorithm, but we don't actually know the full details of how it works. It's a black box—trusted, but not fully understood by most users. This marks a shift in our relationship with information: we're now relying on an automated process to curate and filter the vast amounts of data available to us.

Network. But with people

What if, instead of just sharing information, people themselves could be ON the internet? Individuals began creating personal home pages (remember those .php sites?) and weblogs—blogs for short. But these were still separate islands of information.

What if there was a place where everyone could write something and instantly share it with their friends? This additional layer became known as Web 2.0—the internet, but with humans. Share your thoughts (Twitter), links (Delicious), pictures (Flickr), videos (YouTube, Vimeo), locations (Foursquare), lives (Facebook), and reviews (Yelp). Share everything.

Latency: No point in measuring this anymore. It’s instant.

Novelty: Now, nearly everyone can produce content and share it with the world, creating a continuous stream of new ideas and information.

Authority: Authority has flown out the window. Everyone has an opinion, and you can choose your own "God" to trust—whether that’s an influencer, a friend, or a stranger.

Precision: A single story now has thousands of variations, each shaped by the perspectives of different individuals.

Web 2.0 marked a fundamental shift in the internet’s evolution, transforming it from a repository of information to a dynamic, interactive space where people could connect, share, and create in real-time. The internet became not just a tool, but a reflection of human society itself, with all its diversity, complexity, and chaos.

Everything, everywhere, all the time

The introduction of smartphones provided the final push that transformed how we produce and consume information. Now, we’re creating and accessing all kinds of content in real-time, from anywhere on the planet.

WTF is happening here? These might be the words of your great-grandparents if they had to live one day in the shoes of today’s youth. The pace and volume of information are staggering. Television, radio, the internet, social media, apps—everyone is creating content, it's being reproduced instantly, and countless ideas are floating around. Not long ago, humans dealt with limited information and ideas, mostly from trusted sources. Or the trust wasn't that important all together. Now, we have TikTok, which can present you with something "new" every 60 seconds—for eternity. Facebook, Instagram, Youtube Reels, Linkedin are competing with their own infinite scrolls. And then you have messaging apps with your own bubbles.

Latency: It’s instant.

Novelty: Endless. There’s always something new, every moment.

Authority: Who knows whom to trust anymore? Authority has become highly fragmented.

Precision: It’s still somewhat present, as each piece of content can be traced back to some source, but the overwhelming volume makes it difficult to discern what’s accurate.

The smartphone era has pushed us into a reality where information is not just abundant but overwhelming. We’re constantly bombarded with new content, ideas, and perspectives, making it increasingly challenging to navigate this sea of information. The question now is not just what to consume, but how to manage it all.

Large language models

We now live in an age of overwhelming information—an unimaginable amount of data is being generated and processed in real time, continuously transforming into 0s and 1s. As humans, we've reached a point where we can no longer keep up. Search engines “kind of” help us navigate this vast sea of information, but even they can't fully manage the enormity of it—and neither can we. All sorts of algorithms are analysing us.

Every major technological advancement has reshaped how we interact with information. With each new tool, more people have become "information workers"—individuals whose primary job is to engage with, organize, and manipulate information.

Now, AI and generative models are causing another major shift. Just as we once "agreed" to rely on books for knowledge, understanding that we don't need to memorise everything ourselves, and we accepted that we don’t need to understand how computers work to harness their power, we will need to strike a similar agreement with AI. To truly harness their power, we need to understand how they work, their limitations, and their biases.

Part II - Compression of knowledge.

Some good ol’ books to check:

The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

The Revolt of the Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium